This is perhaps one of the most common misconceptions surrounding the Iditarod, and one that I realized only a few years ago.

Although both the Serum Run and the Iditarod are of great importance, and share some of the same route, trails, and stops, they are two events that are completely separate. The Iditarod is not run to commemorate the Serum Run of 1925. This has occasionally been misreported before, but as both Dan Seavey and Dick Mackey reiterated to me in talking with them, they have nothing to do with each other.

When the Iditarod race was first organized by Joe Redington Sr., it was meant to serve two purposes. According to the book chronicling his life, Champion of Alaskan Huskies by Katie Mangelsdorf, his first goal was to get the Iditarod Trail recognized as a national historic trail, and second, to help continue and promote the use of sled dogs throughout Alaska.

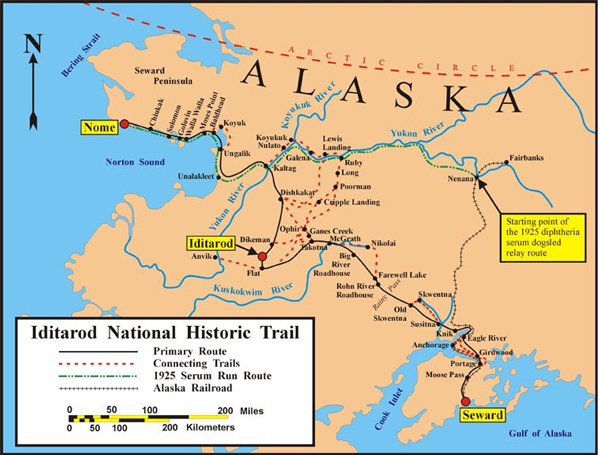

Historic Iditarod trail map. (Map via BLM)

The Iditarod Trail had been used for years since its establishment in 1908 when gold was discovered at Iditarod. Used only in the winter, Harry Revell didn’t make the initial mail run from Seward to Iditarod until 1914, prior to then it was used mainly as a supply route. It served as a route for mail and supplies until 1963. By then the Iditarod trail had developed into an extensive route system, reaching all the way to Nome, and including connecting trails that reached all the way to Ruby and Anvik. However, as both technology and modes of transportation improved, the trail was being used less and less. The final delivery using sled dogs was made in 1963. At that point, the dogsled was completely replaced by the airplane and snow machine as the most sensible modes of transportation. Yet, in 1978, Congress established the Iditarod as a National Historic Trail, thus fulfilling Redington’s first goal. You can read more about the early history of the Iditarod Trail here:

https://www.blm.gov/sites/blm.gov/files/Programs_NLCS_Iditarod_Trail-Historic-Overview.pdf

In the 1960s, the snow machine (or snowmobile) started to replace sled dogs as the main mode of transportation. But the reason Redington moved to Alaska was because he wanted to mush dogs, and didn’t want them to disappear into the history books. As Dick Mackey told me in an interview, “sled dogs were being replaced by snow machines, and we wanted to show that snow machines are fine, but machines break down. Dog teams don’t.” In essence, dogs are more reliable, and without a way to keep them in use, they may begin to disappear too. Therefore running the Iditarod became even more crucial. When the first race was made official in 1973, Joe Redington Sr. had started to work on his second goal; saving the Alaskan sled dogs. The first few years of the Iditarod Dog Sled Race were a bit of a struggle. In 1973, Joe had to put up much of his own money to make his dream a reality. Even then, after the race was completed, he still had to ask Dan Seavey if he could borrow some money to top off the purse. An act that Seavey was happy to do. It was because of these initial efforts and selfless acts of those involved, that the Iditarod grew into the annual race that it is today. This year there are already 63 mushers from all over the world who have signed up to run The Last Great Race®. This shows that Joe has been able to accomplish his second goal. Because of his efforts, according to Mackey, “I think that if it comes right down to it, we have saved the Alaska sled dogs.”

Honoring the Serum Run:

There is a separate relay that was run more recently to commemorate the Serum Run. In 1995, Joe Redington Sr. helped organize the 1995 Commemorative Serum Relay Race.

Map of the Serum Run from The Cruelest Miles, by Gay and Laney Salisbury (W.W.Norton & Co., 2003)

This race was to have much of the same intent as the original 1925 life saving mission; rescuing the town of Nome from an outbreak of Diphtheria. He joined a statewide “Shots for Tots” program and organized mushers to deliver immunizations by dogsled, to the villages along the route of the Serum Run. The goal was to have 100% of children age 0-2 immunized.

Today, this relay is named after famed Antarctic explorer and 13-time Iditarod racer Norman Vaughn. “In 1997 [Norman Vaughn] organized the annual 868-mile Serum Run from Nenana to Nome, Alaska. This commemorates the 1925 dash to Nome by the fastest village dog teams to deliver diphtheria serum to save Nome.” http://www.normanvaughan.com/races.html Today, the race is called the Norman Vaughn Serum ‘25 Run.

Now more than ever, comparisons can be made between the Iditarod race and the 1925 Serum Run. As we are faced with today’s reality of COVID-19 and a global pandemic, medical professionals are in a rush to develop a vaccine and save lives. There are clear connections that can be made between our current situation and the diphtheria outbreak in Nome, when officials were also in a rush to distribute a life-saving antitoxin. The same determination and sense of urgency that was demonstrated by the relay teams in 1925 is also seen in the scientific and medical communities of 2020 as they race against the clock to bring us safely through this pandemic.

Teachers: Check out this lesson to have students examine the different maps of the Iditarod race, the Serum Run, and the historic Iditarod Trail. There is even a modern day connection for the students to work through a hypothetical scenario of a COVID outbreak in an Alaskan town, and finding the best route to get there based on the history and what they learned about the maps. This COULD be done virtually, although recommended in person. Analyzing the Historic Routes of Alaska

- Visiting Balto at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History

- Visiting Togo at Iditarod Headquarters